This post will be amended.

I humbly present the following unified model of the modern business corporation.

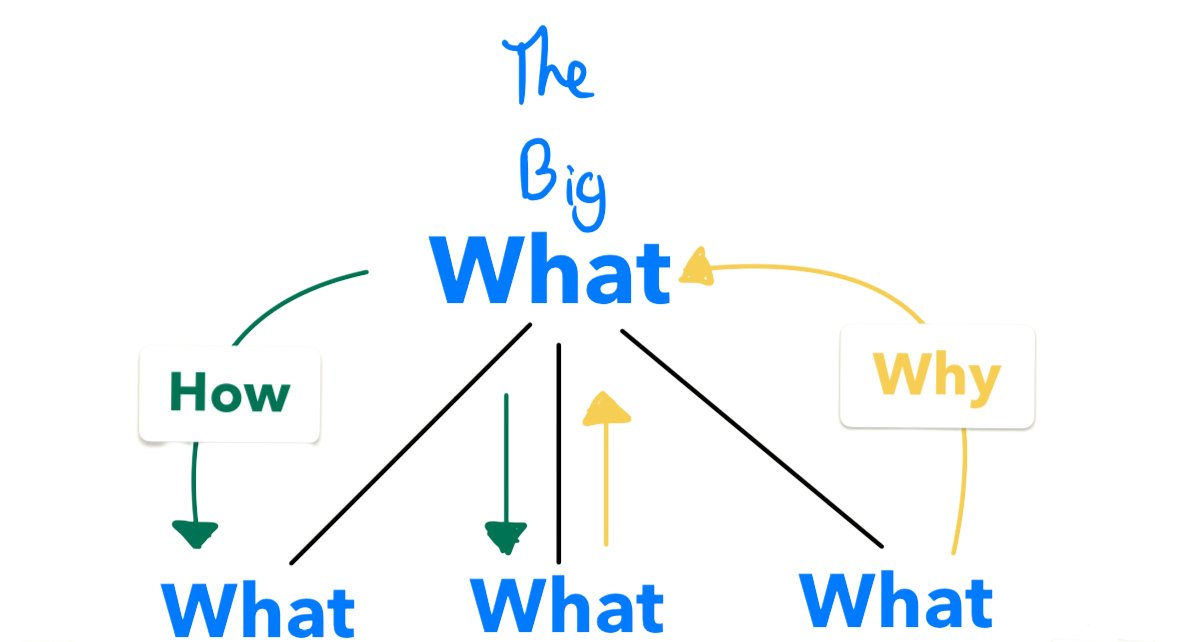

The effective corporation can be understood as a series of interconnected Whats, defined broadly as the endeavors or activities of the corporation (aka firm, business, company). In this model, each What is a node connected to other nodes by bi-directional How-Why arcs. How arcs cascade down the tree and Why arcs coalesce up.

If we’re talking business, and we are talking business, the Big What (aka The Top What, the Granddaddy What, etc.) is the first point of differentiation from other businesses. It’s the raison d’etre.

What about the Big Why? The Big Why will either be very generic (e.g. “to make money” or “to make the world a better place”) or very personal (e.g. “I swam with a dolphin and it told me that my destiny is to revolutionize the SaaS industry with AI.”) In either case, it’s usually irrelevant for differentiating the organizational tree.

To build the tree from the Big What, ask “How?” and keep asking “How?” until you don’t know anymore. If your smallest Whats are still too big for you to understand which activities to pursue, then hire people who know how to break them down further.

That’s pretty much it. The words below will be about the implications.

An Example

Let’s say you want to build some B2B SaaS with the homies. The Big What could be “Create an AI software product that will update Salesforce so your sales force doesn’t have to.”

Now, repeatedly ask How to build the tree.

How? Well, to be a business, you’ll have to sell the software to customers.

How? a) You’ll build a product that businesses with money will want to buy. b) You’ll need a way to get their attention. c) You’ll need to let them test the product and convince them to pay us money.

Each sentence above represents a chunk of work, a What. The chunks immediately underneath “Sell Our Software” represent the organizations Product/Eng, Marketing, and Sales, respectively.

If you continued down the tree, and if the company got big enough, you’d eventually write down things like “marketing budget reconciliation” and have employees with important-sounding titles like “Head of Marketing Analytics, Website” or “VP, Product Marketing.”

General Principles

To move up, ask Why; to move down, ask How.

The Theory of Whelativity: All Whats are relative. One person’s What is another’s Why is another’s How, depending on the vantage point.

Beware Whys masquerading as Hows: Due to the Theory of Whelativity, people can bend Whats and Whys to serve their own perspective. I heard someone recently say, “Product managers define What gets built, engineers figure out How to build it, and product marketing articulates Why the customer should be interested.” Alarm bells. In this framing, product marketing is figuring out How to market to the customer, but the speaker has cleverly framed their How as a Why to make it seem more important.

Common failure modes: The most common failure modes in this model of the organization are disconnection (a How error) and perceived disconnection (a Why-communication error).

In the first case, workers are working on tasks that do not serve the Big What. Somewhere above them in the tree, a leader made a How error. They are rowing (or to keep it aboreal, they are “growing”) in the wrong direction.

In the second case, workers are working on tasks that they do not perceive to be serving the Big What (even though they actually are.) The penalty for perceived disconnection is lower motivation and eventually lower output. A popular term around perceived-disconnected teams is “siloed.” These teams feel a lack of purpose because the Why of their work was not properly communicated to them.

The further “up” a mistake is made, the more of the tree is affected (and the more will eventually need to be pruned, or “re-org’d.”)

The Seduction of How

Let’s say you are the smartest and best business founder. You’re talented, you’re hardworking, you’re crushing it (even when it doesn’t feel that way on the inside). You choose the right Big What (right problem, right market), and you begin to build your company. Because you’re so smart, you know the Hows all the way down: you could do every job in the organization better than the person who actually does that job. You can clearly see where your involvement in the tactics would improve the business, so you get involved in smaller and smaller Whats. Because you know How.

This is bad for a number of reasons — well-documented perils of micromanagement, you’ll get tired — the worst of which is the people whose jobs you’re doing cannot do yours, and yours is more important than theirs. You are responsible for getting the big Whats right, hiring the right people to define the Hows, and painting the right vision that connects employees to the big Whys. Mistakes and missed opportunities that far up the tree hurt the entire organization. The opportunity cost of handling the smaller Whats is far too high to justify the improved outputs in the lower branches.

Know Your Why

The admonition to “know your why” is a common one in self-help literature, and it’s at least as important inside corporations to help employees understand their Why.

The people doing the Whats, no matter how many levels down, should be able to Why their way back up to the ultimate aim: the Big What. The most effective organizations define and communicate their Whats and also their Whys and Hows up and down the tree.

At the organizational level, this definition and communication is called “planning” or “alignment.” At the individual employee level, it’s called “motivation.”

A famous (apocryphal?) example from American history comes from The Space Race. President John F. Kennedy was touring the NASA facility when he met a man carrying a broom down a hallway. The President asked this man what his responsibilities were, and the janitor responded, “I’m helping put a man on the moon.”

Acknowledgements

This post owes a huge debt to Salesforce’s annual alignment exercise, the V2MOM (Vision, Values, Methods, Obstacles, Measures). All these years later, all the letters are still there at the top of my head and the tip of my tongue.

Notes

* It is the one just below (via a How arc) “solve a problem for customers with a willingness to pay for a solution.”

** Value-signaling through publicizing the Big Why can be good for business, either directly — through appeal to shareholders or customers — or indirectly through recruitment and talent

*** Plus, expanding the framework runs us into the problem of unbounded Whys. Grappling with unbounded Whys would require ascension to the metaphysical, a flight of fancy to which I am not qualified to do justice.

E.g. “Why does the business exist?” “To make the world a better place” “Why?” “To help mankind progress” “Why?” “For those of us with the privilege to do what we wish, such is our duty on this mortal coil.”

The point is: there can always be another Why, which I discovered and thought was hugely clever when I was 6.

Parent: Eat your peas.

Me: Why?

P: Because they’re good for you.

Me: Why?

P: Because they’ll help you get big and strong.

Me: Why?

P: Because the amino acids, vitamins, and nutrients will help you grow big and strong.

Me: Why?

P: Because your body needs these nutrients to build and repair tissues, produce energy, and support your immune system to fight off illnesses.

Me: Why?

P: Because our bodies are made up of cells that need these nutrients to function correctly and to keep you feeling energetic and strong.

Me: Why?

P: These substances, like vitamins and minerals, are involved in critical processes in the cells, such as creating energy, protecting against damage, and making new cells. For example, peas contain vitamin C, which helps protect your cells and keeps your skin healthy.

Me, giving up, not for lack of Whys but lack of stamina: Fine, I’ll eat my peas.

(Parent can pull the ripcord at any time with “Because I said so.”)