I’m thinking of a duck.

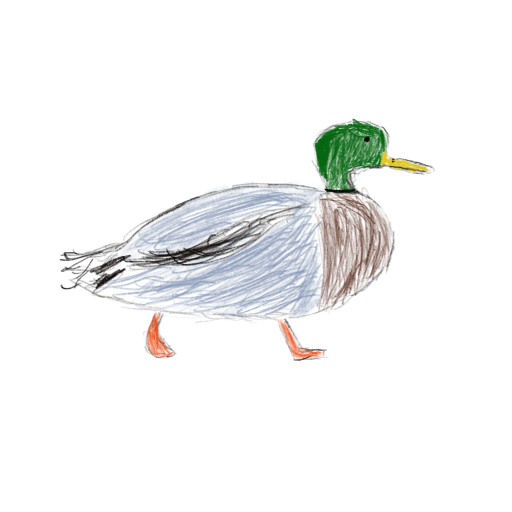

Not just any duck. It’s a specific duck that looks sort of like this:

Now, imagine that I want you to be able to hold this duck in your mind the same way I’m holding it in mine. It doesn’t have a name yet, in case you wondered, so feel free to name it yourself.

The above drawing, amazing though it may be, is not the duck. It’s a poor approximation; the duck in my head is much-better looking. But how can I communicate the true essence of the duck to you?

It is here that I encounter The Communication Problem.

The problem is that I lack the tools to losslessly convey the duck from my mind (across the gulf between our respective subjective consciousnesses) to your mind. Put simply, we cannot communicate directly. The language and symbols we use are, like the drawing above, indirect and incomplete abstractions.

The implications of the Communication Problem are sobering: I’ll never fully understand you, you’ll never fully understand me, and we should think about how we want to handle that.

Paddling Furiously, Not Getting Far

Let’s think some more about the duck.

As I mentioned previously, I have a beautiful image of a water bird in my head. Thanks to my academic training, I know this bird is, in English, called a “duck” - my academic training is also responsible for my understanding of “bird,” “water,” and “academic.”

The image I have in my mind delights me, and so I wish to share it with you, so that you may also be delighted. But how can I do so?

I could try to describe it. Because you’ve read this far down on an essay in a language that I know to be called English, I can make the assumption that you know how to decode the English word “duck”, so I might encode the information by saying, “I’m thinking of a duck. Not just any duck.”

You might then indicate you’d like to know more about this duck. Now, due the lack of duck-specific-scholarship in my life, my descriptive powers are nearing their limit- I’m not sure what are the important attributes for describing a duck and differentiating one duck from another.

I know, I’ll draw the duck!

When I’m finished, I’m actually pretty proud of the drawing but, upon review, it really bears very little resemblance to the positively regal bird strutting around in my mind palace. You’ve probably got a something resembling a duck in your head now too, but it’s not the duck.

We’ve gotten close, but close enough? It’s difficult to be precise about what “close enough” means without agreement on the goal (outside the scope of this essay). And this difficulty with the duck makes me less than confident that I’ll be able to convey more important, complex ideas, like the project I want to work on with you or what it feels like to be me.

Seeking the Common

At the risk of stating the obvious, we humans desperately crave the reassurance and the feeling of drawing closer to each other that communication affords. Alfred Adler, founder of the school of individual psychology, observed that humans seek, above almost all else, a community feeling, a feeling of belonging.

Communication may be understood as that process through which community (and its feeling) is formed - both words share the Latin root communis, meaning “common.”

Sadly, each of us exists at the center of our own subjective universes and is therefore fundamentally alone. We are conscious enough to desire and aspire to direct connection, yet we’ll always fall short.

The crux of the Communication Problem is that we cannot communicate with each other directly. Now, it should be said that we humans do a pretty bang-up job with indirect methods, such as speech, writing, art - we get close. But ultimately, these are blunt instruments, abstractions, and approximations. Try as we might, we will bump up against fundamental constraints on the fidelity of information we can transmit to one another.

There’s Layers

The more layers between the communicator and the recipient, the more is “lost” in transit.

Each layer requires an encoding on the part of the communicator (and for each encoding, a later decoding on the part of the recipient).

If the highest fidelity form of communication is (as-yet-fictional) temporary cohabitation in someone else’s brain, each step away from that ideal means more meaning loss.

The Problem is particularly acute for written asynchronous communication, such as email, text messages, or hand-written love letters.

The above is meant to represent what is lost in transit for a simple text message. Through the process of encoding, the communicator must “whittle down” what they wish to communicate so that their message will fit into a mutually accessible medium. Upon receipt, the recipient then must decode and build back up the message from symbols on a screen into an idea or feeling that can be held in the brain.

The result is that the idea/feeling as understood by the recipient will necessarily differ from the original idea/feeling of the communicator.

Because each layer charges a tax on meaning, communication media that require the traversal of fewer layers thereby retain more of a communique’s original meaning.

The Magic of Voice Notes

Which brings us, finally, (from ducks to the existential) to voice notes.

Voice notes, at first, felt too intimate. Listening to one felt as though the sender was sitting very near to me, speaking softly into my ear.

Initially, I resisted, answering inbound voice notes with typed replies, because change is hard and behavioral inertia is real. Over time, I’ve come to embrace the medium more and more, so much so that I started to think about why.

Voice notes remove the expensive encoding and decoding of words to text and vice versa. Delivered through the same interface as traditional text messages on platforms like iMessage and WhatsApp, they convey more of the original meaning than their nearest neighbors.

And they retain the benefits of asynchronous communication: you don’t need a dual coincidence of availability, you can take time to craft a thoughtful response, etc.

I have become known to pour my heart out via voice notes in ways I couldn’t type and would find difficult in synchronous communication (face-to-face or speaking on the phone) - a sort of Voice Note Confessional, as it were. This phenomenon also fascinated me.

I think this (over)sharing can be partially explained by illusion of impermanence that emboldens us to speak aloud things we’d be reluctant to type - only an illusion of course, as voice notes can be just as easily forwarded and saved as typed messages.

But I think because voice notes remove layers of encoding and decoding, voice-noters feel confident that more of the meaning in their messages will be retained, confidence that in turn encourages them to share more information.

At least, I think that explains the behavior of voice-noter Yours Truly.

In Conclusion

So what should we do, given we cannot communicate directly and therefore are prone to feeling deeply and perpetually misunderstood?

Acknowledging the intrinsic limits of human communication is helpful, I think, for setting healthier expectations about what is possible and what we can hold in common.

It’s pretty discouraging to know that I will never fully know, nor be fully known by, anyone else. However, I can take heart in the understanding that I am not alone in this, because this we have in common. I can be grateful for what I do know and for those who’ve sought to know a bit about me.

Communicating effectively is hard in a fundamental way. I believe that grasping why it’s hard makes it easier to appreciate when you hear or are heard, when you know or are known, when you are strengthening a community and that community is strengthening you… and when you receive a 10-minute long voice note.

What did you name the duck?